EL REVERSO INEVITABLE DE LA CONSTRUCCIÓN

Verónica Rosero

Publicado originalmente en: http://www.metalocus.es. METALOCUS, Revista Internacional de Arquitectura, Arte y Ciencia. España. Junio 2011. English version: "The inevitable face of construction"

Pruitt-Igoe representó un supuesto triunfo del postmodernismo sobre el modernismo, y su discurso venía acompañado de la memoria como el punto central del debate del pensamiento postmoderno, una memoria enraizada en la nostalgia de las ruinas de la antigüedad. Este debate se produce en un contexto en el cual la voluntad de realizarse a través de los medios, de ser “inmortal” se vuelve compulsiva. En 1980 un grupo de artistas llamado Teilbereich Kunst hacen referencia en su exposición al nombre Heróstrato. Sentenciado a muerte 2000 años atrás (365 dC), tras quemar el templo de Artemisa en Ephesos, este personaje cometería tal atrocidad con el único fin de asegurarse un lugar en la historia. Heinz Schutz compara a Heróstrato con Pruitt-Igoe: Ruina = Fama[6]. Ambos condenados al olvido, entraron en la historia irrefutablemente.

++++++++++

Publicado originalmente en: http://www.metalocus.es. METALOCUS, Revista Internacional de Arquitectura, Arte y Ciencia. España. Junio 2011. English version: "The inevitable face of construction"

Giovanni Battista Piranesi

“Roma

quanta fuit ipsa ruina docet”

Lo que fue Roma, su grandeza inconmensurable,

queda patente en la calidad de sus restos. [1]

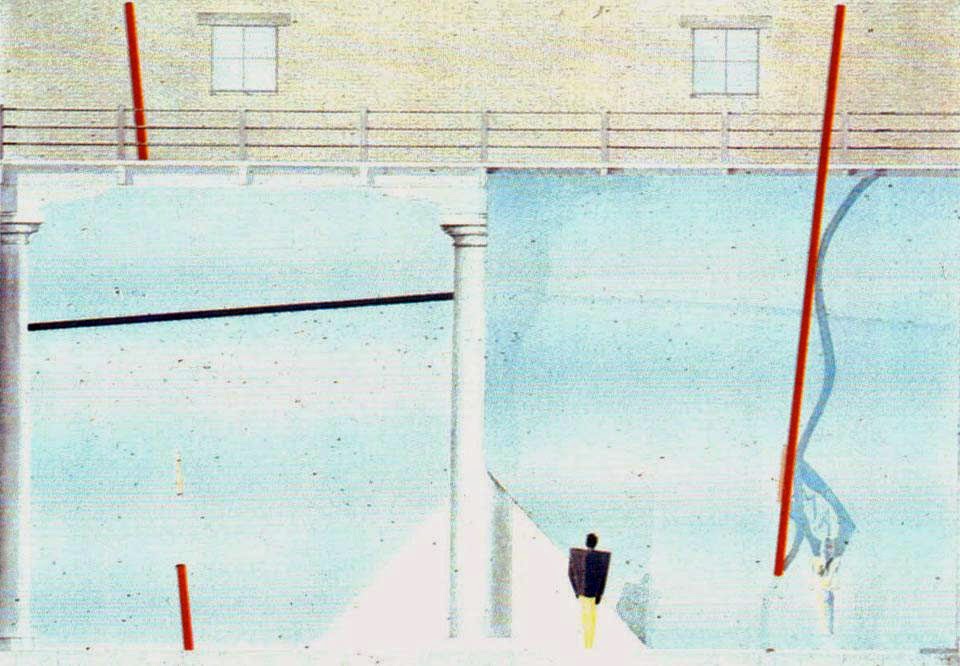

La ruina, no sólo es la reliquia de un pasado ideal, también

representa la muerte natural de la arquitectura. Su importancia se marcó en el

mundo renacentista cuando se miraba con nostalgia las ruinas del mundo

greco-romano. La conciencia arqueológica estaba direccionada hacia ellas; tanto

así que el culto a las ruinas engendró un género específico, la “pintura de

ruinas”, como es el caso de G.B. Piranesi o Hubert

Robert, quienes encontrarían en las ruinas la inspiración para su trabajo.

“Architectural Landscape

with a Canal”. Hubert Robert, 1783

Las ruinas invitaban a la emulación del presente, pero eran fundamentalmente

un emblema de la caducidad de las empresas humanas. Sin embargo, esta

degradación lenta y melancólica, no parece obedecer a la dinámica cultural de

la modernidad. Nuestro mundo contemporáneo privilegia la destrucción súbita y

violenta. Las guerras del siglo XX, bajo un paradigma sostenido de destrucción

agresiva, arrasaron poblados enteros, lo que produjo cambios fundamentales en

la arquitectura y en el urbanismo.

A inicios del siglo XXI fuimos testigos del atentado de las torres

gemelas. Este suceso que produjo un impacto emocional superior al de ninguna

otra destrucción arquitectónica, recuerda en conjunto al fuego y azufre sobre

Sodoma y Gomorra, las llamas o rayos que según relatos derribaron la torre de

Babel, los infernales edificios volcán fantaseados por El Bosco y al ataque sin

sentido de Guernica. [2] Nada

esperanzador, el siglo XXI llega además de la mano de reales amenazas por el

colapso ecológico y los conflictos bélicos.

Bombardeo de Guernica. Guerra

civil española. 1937

“Guernica”. Pablo Picasso. 1937

Unas décadas atrás, este

recurrente pensamiento apocalíptico podemos apreciarlo en el documental

Kooyaanisqatsi[3] cuyo

director, Godfrey Reggio, produciría el film en la época de pleno debate de lo

postmoderno sobre lo moderno. Koyaanisqatsi, con su claro mensaje moral sobre

el estado de la cultura de las grandes ciudades, y con un velado mensaje

semiótico sobre lo postmoderno, nos deja para el debate un controversial

episodio del documental: la demolición de Pruitt-Igoe[4],

ante la cual, el público somos espectadores omniscientes del espectáculo. Tras

dos décadas de enraizados problemas no sólo socio-económicos, sino también de raza

y de género, Pruitt-Igoe se vino abajo junto con las políticas fallidas de

vivienda que lo generaron. Pocas imágenes en la historia de la arquitectura son

tan impactantes como aquella demolición en 1972. Pruitt-Igoe, icono y mito

arquitectónico a la vez[5],

es la metáfora del Apocalipsis de Koyaanisqatsi, pero es también la fascinación

de la imagen, es la imagen en sí misma, la explosión arquitectónica, la ruina

en pleno momento de creación.

“Pruitt-Igoe”

proyecto de Minoru Yamasaki demolido entre 1972 y 1975. “Pruitt-Igoe”

1968. Niños pintando la zona de juegos como parte de un proyecto escolar. Fuente:

St. Louis Post Dispatch

Pruitt-Igoe representó un supuesto triunfo del postmodernismo sobre el modernismo, y su discurso venía acompañado de la memoria como el punto central del debate del pensamiento postmoderno, una memoria enraizada en la nostalgia de las ruinas de la antigüedad. Este debate se produce en un contexto en el cual la voluntad de realizarse a través de los medios, de ser “inmortal” se vuelve compulsiva. En 1980 un grupo de artistas llamado Teilbereich Kunst hacen referencia en su exposición al nombre Heróstrato. Sentenciado a muerte 2000 años atrás (365 dC), tras quemar el templo de Artemisa en Ephesos, este personaje cometería tal atrocidad con el único fin de asegurarse un lugar en la historia. Heinz Schutz compara a Heróstrato con Pruitt-Igoe: Ruina = Fama[6]. Ambos condenados al olvido, entraron en la historia irrefutablemente.

La destrucción arquitectónica y urbana ha venido obedeciendo a diferentes

causas o invariables, ya sea guerras, desastres naturales, o demoliciones

planificadas. Las referencias históricas sobre la aniquilación violenta de

ciudades y poblados, son extensas. Pero lo primordial, aunque abruptamente

rescatable, es que estas destrucciones por fatídicas o adversas, han encontrado

su sitio en nuestro imaginario cultural y varias de ellas han sido artífices de

prometedores episodios de progreso.

Las construcciones, las empresas humanas son más frágiles de lo

que parecen; vastos poblados y grandes monumentos han sido susceptibles de ser

ensordecidos y su imagen es absolutamente lejana, por ejemplo, a aquellos

románticos cuadros de Hubert Robert. Las huellas físicas y psicológicas y el devastador paisaje de estas ruinas

contemporáneas no representa, como en la antigua Roma, la grandeza

inconmensurable de su cultura, representan la fragilidad de la actual población

de nuestro mundo globalizado ante la naturaleza y ante su propia existencia.

Sin embargo, aunque ya no existe la melancolía ante la ruina

desgastada por el tiempo, y sólo está la memoria sobre escombros plasmados en

una imagen mediática, virtual y persistente, es pertinente hablar de

destrucción, dolor, vacío, para poder abordar su reverso: LA CONSTRUCCIÓN. Esa (re)construcción que se realiza

inevitablemente a través de la MEMORIA.

“Koyaanisqatsi”. Portada Banda Sonora

[1]

SERLIO, Sebastiano. “I sette libri dell’ archittetura” en: RAMÍREZ, Juan Antonio. “De la ruina al polvo. Historia sucinta de la

destrucción arquitectónica”. En “Arquitectura Viva”. No. 79-80. Año 2001. Pág.

100

[2]

RAMÍREZ, Juan Antonio. Op.

cit (1) Págs. 100-105

[3] REGGIO, Godfrey. “Koyaanisqatsi: Life out of

balance”. Género documental. 86 min. Estados Unidos. 1982

[4] Proyecto de vivienda colectiva del

arquitecto Minoru Yamasaki, ubicado en St. Louis, Missouri, cuya construcción

culminó en el año 1954.

[5]

BRISTOL, Katharine. “The Pruitt-Igoe myth”. En “EGGENER, Keith. “American

architectural history: a contemporary reader”. Ed. Routledge. Nueva York. 2004. Págs. 352-364

[6] SCHUTZ, Heinz. “Fame + Ruins”. En “Architectural

Design”. No. 154. Págs.

54-57. Noviembre 2001

++++++++++

THE INEVITABLE

FACE OF CONSTRUCTION

Verónica Rosero

METALOCUS. “In Treatment”. June 2011.

___________________________________________________

The

greatness of Rome is still present on the value of its remains.

Ruins are not only the reminder of an

ideal past but also a representation of the natural death of architecture. Its

importance was obvious during the Renaissance when the Greek-Roman ruins were

seen with melancholy. Archaeological awareness was directed towards them; to

the extent that its admiration generated a specific genre, the “painting of

ruins”, as the ones made by G.B. Piranesi or Hubert Robert who found in them

inspiration to create their work.

Ruins were an invitation to the

reproduction of the present, still; they were essentially a symbol of the

fading of human companies. Nevertheless, this slow and sorrowful degradation

doesn’t seem to obey to cultural dynamics of modern times. Our contemporary

world grants privilege to sudden and violent destruction. Twentieth century

wars based upon a sustained model of aggressive destruction devastated entire

settlements, which later produced essential changes in architecture and

urbanism.

In the early 21st century we all

witnessed the attack to the Twin Towers. This episode caused on people

worldwide further emotional impact than any other architectonic destruction and

reminded us, altogether, of Sodom and Gomorrah fire and sulfur, the flames or

rays that according to old stories demolished Babel Tower, the hell-like

volcano structures imagined by “El Bosco” and Guernica´s absurd attack[2]. Absolutely unhopeful, the

21st century comes hand in hand with real ecological threats and wars.

Some decades ago, such

persistent apocalyptic thinking could be observed in the documentary film Kooyaanisqatsi[3]. Its director, Godfrey

Reggio, would produce the film over a period of time in which postmodernism

over modernism was a matter of serious debate. Koyaanisqatsi, with his clear

moral position on the state of the culture of great cities, and with an implied

semiotic message on postmodern issues, leaves us a controversial episode of the

documentary to debate upon: the demolition of Pruitt-Igoe[4], which the audience

watches as omniscient spectators to the spectacle.

After two decades of not

only severe socioeconomic problems, but also ethnic and genre related issues

Pruitt-Igoe failed along with the unsuccessful housing policies from its

generation. Hardly any images in the history of architecture are as impressive

as the ones from its demolition in 1972. Pruitt-Igoe, both architectonic icon

and myth[5], is not only the metaphor

of the Apocalypse of Koyaanisqatsi but also the profound fascination to the

image itself, as it is the architectonic outburst, the remains in the very

moment of their creation.

Pruitt-Igoe suggested an underlying

victory of postmodernism over modernism, and its speech came along with memory

as the main point of debate of postmodern thinking. It was about the memory

embedded in the nostalgic feelings of ancient ruins.

This debate takes place inside of a

context in which the willingness of feeling fulfilled through the media, of

being “immortal” becomes compulsive behavior.

In 1980 a group of artists called

Teilbereich Kunst, made reference to Herostratus in their exhibition. Sentenced

to death 2000 years ago (365 bC), after burning the temple of Artemisa in

Ephesos, Herostratus committed such atrocity with the unique aim of ensuring

his place in history. Heinz Schutz compares Herostratus with Pruitt-Igoe: Ruins

equals Fame[6]. They both were condemned

to forgetfulness; nonetheless, they undeniably became part of History.

Architectonic and urban destruction

has been brought about by different factors or causes such as natural

disasters, wars, or deliberate demolitions. Historical references on violent

towns and cities destruction are largely widespread. But what is fundamental,

though abruptly evident, is that such fatal and undesirable destructions have

found their place in our cultural minds and many of them have become the

origins of promising episodes of progress.

Constructions and human

companies are far more frail than they seem; vast towns and great monuments

have been vulnerable of being deafened, and their image is completely distant,

for instance those romantic paintings by Hubert Robert. The physical and

psychological traces and the devastating landscape of these contemporary ruins

do not represent, as in ancient Rome, the incommensurable greatness of their

culture. In contrast, they represent the weakness of current population, of our

globalised world facing nature and human existence itself.

On the other hand, even if that

feeling of melancholy of ruins worn away by time no longer exists, and there is

merely the memory of wreckage embodied in a virtual and persistent image of the

media, it is relevant to talk about destruction, pain, emptiness; to be able to

approach its inevitable face: CONSTRUCTION, that (re)construction that is

inevitably made through MEMORY.

[1]

SERLIO, Sebastiano. “I sette libri dell’ archittetura”. In: RAMÍREZ,

Juan Antonio. “De la ruina al polvo. Historia sucinta de la destrucción

arquitectónica”. In “Arquitectura Viva”. No. 79-80. Year 2001. Pg. 100

[2] RAMÍREZ, Juan

Antonio. Op. cit (1) Pgs. 100-105

[3] REGGIO, Godfrey. “Koyaanisqatsi:

Life out of balance”. Documentary film. 86 min. United States. 1982

[4] Social housing project by the

architect Minoru Yamasaki, located in

St. Louis, Missouri, whose construction was finished in 1954.

[5] BRISTOL, Katharine. “The

Pruitt-Igoe myth”. In “EGGENER, Keith. “American architectural history: a

contemporary reader”. Ed. Routledge. New

York. 2004. Pgs. 352-364